Ordnance Corps History

The History of Ordnance in America

By. Karl RubisOrdnance Branch Historian

The Ordnance Branch is one of the oldest branches of the U.S. Army, founded on 14 May 1812. However, the duties and responsibilities of the profession date back to the colonial era. In 1629, the Massachusetts Bay Colony appointed Samuel Sharpe as the first Master Gunner of Ordnance.

Just sixteen years later, the Massachusetts Bay Colony had a permanent Surveyor of Ordnance. His responsibility was to deliver powder and ammunition to selected towns, recover weapons from militia members, receive payment from those who lost weapons, and provide periodic reports to government officials to guide the purchase of firearms, powder, and shot. Although, each colony developed a militia system in which members were required to provide their own weapons and initial amount of gunpowder and shot, colonial Ordnance officials provided a logistical depth for any type of sustained operations.

The American Revolution established the general outlines of the future Ordnance Department. General George Washington, the commander of the Continental Army, appointed Ezekiel Cheever, a civilian, to the Commissary of Military Stores to provide Ordnance support to his army in the field in July 1775. By mid-1779, all the field armies had Ordnance personnel travelling with them. These men, civilians and soldiers, served as conductors of a travelling forge for maintenance, ammunition wagon, and an arms chest. Each conductor led a section of 5-6 armorers to repair small arms. The Continental Congress’ Board for War and Ordnance created the Commissary General for Military Stores to establish and operate Ordnance facilities in an effort to alleviate the dependence on foreign arms purchases. Colonel Benjamin Flower led the Commissary from his appointment in January 1777 until his death in May 1781. Ordnance facilities were established at Springfield, MA, and Carlisle, PA, for the production of arms, powder, and shot. After the war, the sustainment elements were disbanded and the authority for procurement and provision of all things military was transferred to the Office of the Purveyor of Public Supplies located within the Treasury Department.

Early Republic

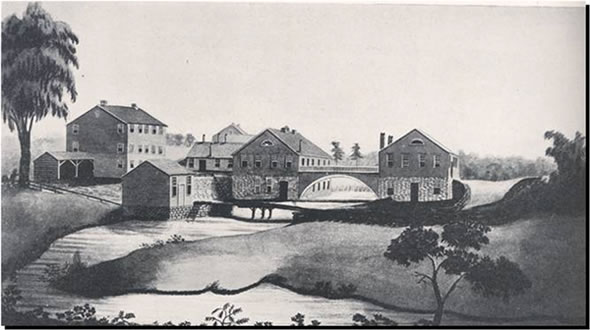

In the first half of the 19th Century, the Ordnance Department played a crucial role in the burgeoning Industrial Revolution and helped to establish the “American System of Manufacturing”. One of the most significant achievements was the establishment of two federal armories; Springfield Armory in 1795 and Harpers Ferry in 1798. Per congressional direction from 1794, each armory staffed a civilian superintendant and a master armorer.

These two armories served as a nucleus for technological innovation for the young republic. Inventors such as Eli Whitney and Simeon North developed the methods and means for mass production through interchangeable parts and refined technology in milling machinery.

By the dawn of the War of 1812, the Secretary of War recognized the need for a distinct branch to manage the procurement, research, and maintenance of Ordnance materiel. Decius Wadsworth, previously superintendant of West Point, was appointed a Colonel and given the title Commissary General of Ordnance, later changed to Chief of Ordnance. His ambition, during the war years and afterward, was to simplify and streamline Ordnance materiel management. His staff worked to reduce the variety of small arms and artillery pieces to a few efficient models. In addition, he aimed to develop a cadre of highly trained Ordnance officers who could dedicate their inventive ingenuity to their profession. This effort created a tradition of technological innovation in the Ordnance Department and resulted in a generation of ‘soldier-technologists’; inventors such as Alfred Mordecai, George Bomford, Thomas J. Rodman, and John H. Hall. Indeed, assignment to the Ordnance branch was one of the most sought-after assignments following graduation at West Point.

In 1832, Congress authorized the rank of Ordnance Sergeant. This rank filled the Army’s need to have a highly-trained and experienced Ordnance soldiers at the increasing number of frontier posts and coastal defensive forts. To apply, a soldier had to have at least 8 years of service, 4 of which had to be as a non-commissioned officer, and pass a series of examinations, to include mathematics and writing. Their responsibilities included the maintenance of arms and ammunitions at army installations and the provision of those supplies to armies in the field. This rank continued until the Army Reorganization Act of 1920. Ten of the fifteen Medal of Honor awardees would serve as Ordnance Sergeants during their enlistment.

Mexican War

The Mexican War provided the first real test of the Ordnance Department’s system of armories and arsenals. In 1841, there were two armories and twenty arsenals. Without difficulty, it met the needs of the Army for equipment and supplies to support the multiple campaigns of the Mexican War. Consequently, it did not undergo any major reorganization following the war. In addition to its support role, the Ordnance Department established the Rocket and Howitzer Battery, the only unit in Ordnance history raised specifically for combat duty. The 105 officers and enlisted men were the only ones with the experience to operate the new M1841 12-pound Howitzer and the latest Hale War Rocket. These weapons were still in the testing phase and had not been distributed to the artillery branch for field use. The unit suffered 6 killed and 22 wounded. At the close of the Mexican War, the department numbered 1 colonel, 1 lieutenant colonel, 4 majors, 12 captains, 15 first lieutenants, and 10 second lieutenants, along with several hundred enlisted personnel and approximately 1000 civilians at the armories and arsenals.

Civil War

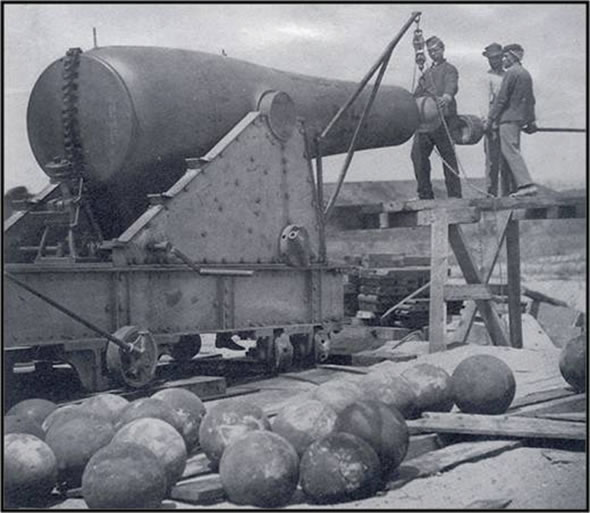

During the Civil War, the Ordnance Department was called upon to arm and equip an army of unprecedented size. It furnished 90 million pounds of lead, 13 million pounds of artillery projectiles, and 26 million pounds of powder for a Union Army of 1 million soldiers. To achieve these impressive amounts, the Ordnance Department civilian staff increased from 1,000 to 9,000 by war’s end. Women were especially sought after to work in the ammunition plants due to the contemporary perception that a woman’s nimble and petit fingers worked better at assembling paper rifle cartridges. Consequently, when there was an explosion (i.e. Allegheny Arsenal in 1862 or Washington Arsenal in 1864), the percentage of female fatalities was very high. In the Allegheny Arsenal explosion, 78 civilian workers were killed, 71 were women.

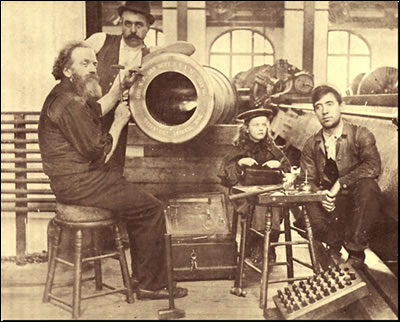

Despite the massive expansion of the army, the official staffing of the Ordnance Department remained small. At the peak of the war, the Department numbered 64 officers and 600 enlisted. Ordnance officers were assigned to divisions and above. For lower echelons, Ordnance responsibilities were tasked out to soldiers who had previous training in smithing or some other Ordnance-related skill. These soldiers remained with their units, but were provided a set of tools from the Ordnance Department. Consequently, thousands of soldiers were detailed to perform Ordnance duties during the war.

A few Ordnance officers accepted line commands, such as Major Generals Oliver O. Howard who won the Medal of Honor at the Battle of Fair Oaks in 1862, and Jesse Reno who was killed at the Battle of South Mountain in September 1862. Most officers, however, remained in the Ordnance Department and rose in rank to serve as Ordnance officers for their commands, to include the Army of the Potomac and other field armies. As was common in other branches of the Army, a considerable number resigned their commissions and joined the Confederate Army (interestingly, most enlisted soldiers remained with the Union Army). Captain Josiah Gorgas resigned his commissioned and assumed a majority in the Confederate Army on 8 April 1861. He was given charge of the new Confederate Ordnance Department based in Richmond, Virginia and would rise to Brigadier General by the end of the Civil War. He is recognized as one of the most able administrators in the Confederate government due to his ability in marshalling an impressive amount of materiel and distributing it to the Confederate Army. It is interesting to note that it was widely anticipated Alfred Mordecai, who was regarded as the most brilliant officer in the Ordnance Department, would quickly rise up the ranks. However, his family was devoted to the Confederacy and he could not conscious the thought that he was constructing materiel to be used against them. After his request for transfer to California was denied, he resigned his commission. The Confederacy offered him a position, but he denied that as well and spent the war years teaching mathematics at a private college in the north.

Spanish American War

Between the Civil War and WWI, the Ordnance Department did not expand to any great extent. Modest improvements in the organization of the Ordnance Department were implemented and scientific research continued, but a general lack of preparedness grew. A full-fledged proving ground was dedicated at Sandy Hook, New Jersey in 1874 and a federal cannon foundry was established at Watervliet Arsenal in 1887. With the arrival of the Spanish-American war in 1898, the Ordnance Department, however, did not have the time to catch up to the swiftness of mobilization and had to ‘muscle through’ its support issues.

The department faced a similar problem it faced in 1861; how to arm and equip all the soldiers during such a sudden increase in size, an approximately ten-fold increase. Regular army troops were equipped with smokeless, bolt-action Krag-Jorgensen rifles, but most volunteer units had the single-shot, breech loading, black powder M1873 Springfield. In a report following the war, Chief of Ordnance Brigadier General Daniel W. Flagler urged that funds be allocated to establish an adequate stock of war reserve munitions, but his recommendations went unheeded. Thus, the United States would have even greater challenges mobilizing for WWI.

World War I

Even though WWI had been raging in Europe for nearly three years, the Ordnance Department had to play catchup when the United States entered the war in April 1917. With only 97 officers and 1,241 enlisted soldiers, the department had a myriad of problems to overcome; no system below the Office of the Chief of Ordnance to coordinate with industry, no plan for mobilizing industry, an inadequate proving ground, no system of echeloned maintenance, a lack of sufficient schooling for enlisted soldiers, and only six armories and manufacturing arsenals at Watervliet, New York; Watertown and Springfield, Massachusetts; Frankford, Pennsylvania; Rock Island, Illinois; and Picatinny, New Jersey.

As the war progressed, the department overcame the lag and matured as an organization and adapted to modern warfare. By the end of the war, the Ordnance Department numbered 5,954 officers and 62,047 enlisted soldiers, with 22,700 of those officers and soldiers serving in the American Expeditionary Force in France. The Ordnance Department established 13 Ordnance districts across the country which had the authority to deal directly with industry and award contracts. By the end of the war, almost 8,000 plants were working on Ordnance contracts.

To offset industry’s reluctance to build new plants, the U.S. government established a system of constructing the factories, but contracting out its operation. By the war’s end, 326 government facilities were operating under the auspices of contractors. This practice was even more successfully employed during WWII. A new proving ground was established at Aberdeen, Maryland. In November 1917, construction began. By September 1918, 304 officers, 5,000 enlisted, and 6,000 civilians were conducting tests on a wide range of munitions.

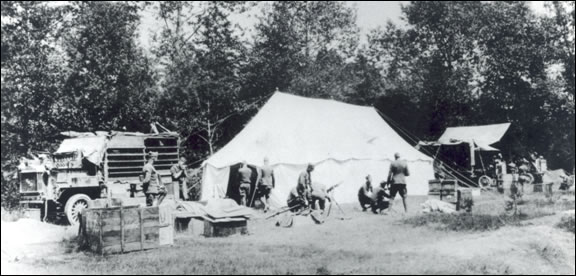

With the experience it gained from the Punitive Expedition in Mexico in 1916, the Ordnance Department established an embryonic system of echeloned maintenance. For major repairs, it established a system of Ordnance repair base shops in France. For maintenance support to the field, the Ordnance Department fielded the Mobile Ordnance Repair Shops (MORS) and Heavy Artillery Mobile Ordnance Repair Shops. These units moved with the division and provided a wide array of support to the line.

To train the new Ordnance soldiers, the Ordnance Department established schools at a wide-array of locations, to include universities, civilian factories, armories, arsenals, and field depots. Eventually, much of the training was consolidated at the Ordnance Training Camp at Camp Hancock, Georgia. By war’s end, more than 55,000 officers and soldiers had been trained at one of these locations, including the six Ordnance schools in France.

Interwar Years

The story for the Ordnance Department between WWI and WWII is filled with both good news and bad news. The decreased budgets limited the amount of money it spent on research, in lieu of maintaining war reserves. In spite of this, several legendary weapons were developed; including the M-1 Garand and the 105mm Howitzer (although, tank development significantly lagged). The development of the Ordnance school system is another success story during the interwar years. Schooling for Ordnance officers and enlisted was streamlined during the period and consolidated by 1940 at Aberdeen Proving Ground at The Ordnance School, a single location where all Ordnance education would occur. This location would be center of the soul of the Ordnance Branch for the next 68 years.

World War II

The Ordnance Department swelled exponentially in WWII and applied the lessons it learned in WWI. The Ordnance Department was responsible for roughly half of all Army procurement during World War II, $34 billion dollars. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s ‘Arsenal of Democracy’ depended on the Ordnance Department to become a reality.

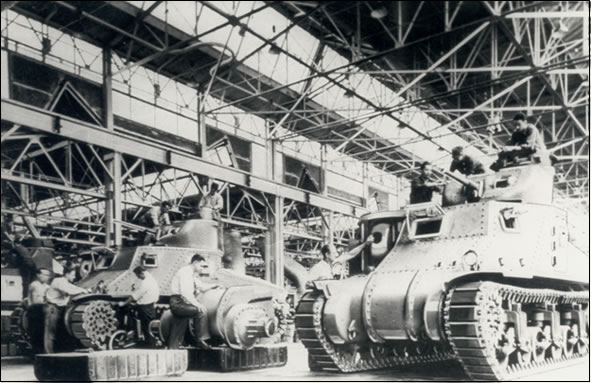

In January 1944, the Ordnance Department accounted for 7 manufacturing arsenals, 7 proving grounds, 45 depots, and 77 government-owned, contractor operated (GOCO) plants and works. Of the 77, all of them focused on ammunition and explosives except one. The Detroit Tank Arsenal was built in eight months while engineers simultaneously designed a new medium tank, the M3. By the end of the war, the Detroit Tank Arsenal built over 22,000 tanks, roughly 25 percent of the country’s tank production during the war. The Arsenal continued to operate as the Detroit Army Tank Plant until 2001.

Ordnance Department strength increased from 334 to 24,000 officers, 4,000 to 325,000 enlisted, and 27,088 to 262,000 civilians, all in an army of approximately 8 million. Women Ordnance Workers (WOWs) accounted for approximately 85,000 of all civilian employees. Ordnance soldiers and civilians worked across the globe, in places as diverse as Iceland, Iran, the Pacific Islands, Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. Aberdeen Proving Ground expanded exponentially and headquartered The Ordnance School, the Ordnance Replacement Training Center, the new Bomb Disposal School, and the Ordnance Unit Training Center.

The Ordnance mission in the field operated on a scale never experienced previously by the Ordnance Department. During WWII, the Ordnance Branch gained its third core competency, Bomb Disposal (renamed Explosive Ordnance Disposal after WWII) added to its previous missions of ammunition handling and maintenance. By war’s end, there were more than 2,200 Ordnance units of approximately 40 types, ranging in size from squads to regiments. The Ordnance Department applied the maintenance lessons it learned in WWI and devised a five-echelon maintenance system ranging from base shop maintenance to organizational maintenance, all in an effort to return materiel to operational status as near to the front line as possible. To complicate the maintenance mission, in 1942, the responsibility for motor transport was shifted from the Quartermaster Branch to the Ordnance Department. The complexity of maintenance for such a wide variety of vehicles spawned several innovations which continue to the present; a system of preventative maintenance and the publication of Army Motors, renamed PS Magazine in 1951. This maintenance challenge remained one of the largest hurdles in WWII.

Korean War

During the Korean War, it would re-establish many functions and methods deactivated after the end of WWII. The Ordnance Corps (renamed such in 1950) re-established the myriad of schools located at Aberdeen Proving Ground to train the increased demand for officers and enlisted soldiers. It re-established its Technical Intelligence Teams which had collected German equipment during WWII for exploitation. During Korea, it exploited captured Russian and Chinese equipment. This materiel would later form a large part of the holdings of the Ordnance Museum.

In Korea, it established a support infrastructure modeled on the one used in WWII, to include echeloned maintenance operations, ammunition handling, and EOD operations. The Ordnance Corps improved this model through standardization to achieve tremendous success in reducing parts and processes, one of the biggest challenges in WWII. Seven standardized engines and transmissions replaced the 18 and 19, respectively, in the previous fleet of vehicles. Stock number reconciliation and an automated stock control system were introduced.

Reorganization & Vietnam

Following the massive reorganization of the Army in 1962 based on the Hoelscher Committee Report, the Ordnance Corps and the office of the Chief of Ordnance was disestablished. The Ordnance branch continued under the direction of the Army’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics. Army Materiel Command assumed responsibility for many of the Ordnance Corps historical functions; research, development, procurement, production, storage and technical intelligence. The Ordnance School was renamed the Ordnance Center and School and came under the direction of Continental Army Command (CONARC). Combat development would be delegated to a new Combat Development Command (CDC).

Despite these changes, Ordnance officers and soldiers continued their core missions of ammunition handling, maintenance and EOD during the Vietnam War. Ordnance support fell under control of 1st Logistical Command which divided Vietnam into four Support Commands. Ordnance units served vital roles under each of these Support Commands. New challenges, however, had to be confronted.

Due to the counter-insurgency nature of the war, EOD units were spread thin; there was no ‘front line’ as it existed in WWII or Korea. The one-year rotational policy produced personnel shortages in some key fields. In the initial years, spare parts shortages and equipment availability rates were low. However, despite these challenges, operational readiness rates increased, and by 1969, exceeded those of previous wars.

Post Vietnam

In 1985, the Ordnance Corps became the first of the Army’s support elements to re-establish itself under the branch regimental concept. The Chief of Ordnance regained responsibility for decisions concerning personnel, force structure, doctrine, and training. This change gave the opportunity for Ordnance officers, soldiers, and civilians to identify with their historical predecessors in their mission of Ordnance support to the U.S. Army.

Since 1991, Ordnance personnel have sustained multiple overseas operations. In Operation Desert Storm, Ordnance personnel supported the largest armored assault in American history! In Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom, Ordnance officers and soldiers supported the Army during a long-term insurgency campaign.

After nearly a century of operations at Aberdeen Proving Ground, the Chief of Ordnance and the Ordnance Corps moved to Fort Lee, Virginia in 2008 as part of the 2005 Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRAC) decision. The new campus is dedicated to train approximately 70% of all Ordnance personnel. The remaining personnel are trained at one of six other locations across the United States. In 2011, the Ordnance Corps consists of approximately 2,700 officers, 3,000 warrant officers, and 100,000 soldiers serving on active duty or with the National Guard or Army Reserve.